‘I simply don’t think that the current Labour leadership understands that its political fate depends on whether or not it can construct a politics, in the next 20 years, which is able to address itself, not to one, but to a diversity of different points of antagonism in society; unifying them, in their differences, within a common project. I don’t think they have grasped that Labour’s capacity to grow as a political force depends absolutely on its capacity to draw from the popular energies of very different movements; movements outside the party which it did not — could not — set in play, and which it cannot therefore “administer”.

‘It retains an entirely bureaucratic conception of politics. If the word doesn't proceed out of the mouths of the Labour leadership, there must be something subversive about it. If politics energises people to develop new demands, that is a sure sign that the natives are getting restless. You must expel or depose a few. You must get back to that fiction, the “traditional Labour voter”: to that pacified, Fabian notion of politics, where the masses hijack the experts into power, and then the experts do something for the masses: later … much later. The hydraulic conception of politics.’

(available at http://www.hegemonics.co.uk/docs/Gramsci-and-us.pdf)

So said Stuart Hall, in ‘Gramsci and Us’, nearly 20 years ago now. New Labour was a response of sorts to that critique, drawing heavily on the late 1980s ‘New Times’/Marxism Today analyses (with which Stuart Hall was himself associated) and attempting a kind of virtual, heavily mediated connection with some of those emerging social ‘movements outside the party’. Many of us now feel that it was a peculiarly selective and distorted response. The de-classed ‘identity politics’ we contributed to the New Labour project, with its worthy emphasis on race and gender and sexuality and sometimes giddy consumerism, came out the other end as Philip Gould’s ‘suburban populism’. Our disintegrating industrial proletariat was reconstituted as their Home Counties petty bourgeoisie.

It may seem now that ‘New Labour is unraveling’, but with the prospect of Brownite renewal offering a variant strain, we should remind ourselves that it’s still there and in government. Gould and others are insisting that the project’s achievements are deep and permanent, in changing the terrain on which their New Tory opponents have to operate and in ‘transforming’ the Labour Party (albeit effectively out of existence). Whatever, New Labour needs to be historically accounted for, even if only so we don’t fall for something like it again. It’s time to ask — what was New Labour all about? Beneath the bossy spin and the rising, scummy tide of sleaze, what has happened in the 15-odd years since New Times?

If we look beyond the glossy rhetoric of ministers and advisers, and the Blair/Brown Punch and Judy show, two particular components of New Labour seem to have come to the fore , and squeezed out the far richer mix which the best of late-period Marxism Today represented:

- An odd kind of shallow, quasi-Marxist determinism, which argues the ‘historical inevitability’ of capitalist globalization with just the same dogmatic fervour and disregard for politics and ideological conflict or real human agency of any kind that marked 2nd International social democracy and later forms of (mainly Stalinist or Trotskyist) leftism. Socialism (or now, globalisation) is coming — all we can or need do is ready ourselves for the new dawn.

- A nerdy awe of information technology, characteristic of people who don’t really understand its scientific or logical bases and that it’s only ever as good as the creative uses that people put it to. This combines, in the writings of Leadbeater, Mulgan et al., with a taste for way-out and ultimately empty ‘new age’ management theory to create an approach to government (or should I say ‘governance’?) more suited to a millenarian cult than a modern, secular political party. The future is coming. It is bright and shiny. If you don’t embrace it you will die… Prepare for lift-off!

But is New Labour really that new? It likes to think and insistently tell the rest of us that it is. The project’s ‘visions’ and ‘models’ are supposedly written on a historical blank sheet. But it incorporates far more old-fashioned, horny-handed Labourism than it cares to admit, even if only because it is grudgingly dependent on the Labour Party electoral machine to “get out the vote” every few years and on the likes of John Prescott to keep the North of England in line. And is New Labour’s “technocratic managerialism” really all that different from the “hydraulic” Fabian expert-ism Stuart Hall referred to in 1987? The cumbersome, room-size, calculating machine may have given way to a palm-top computer, but it’s still churning out the same old exhortation to “trust the experts” on everything from macro-economics to public sector reform and so-called ‘social exclusion’.

I would argue that, within the history of the Labour Party and the ‘broader’ democratic left in Britain, New Labour is simply the latest manifestation of Labourism, that inert, stodgy, defence-mechanism of a fractious, fissured working class firmly, grimly entrenched within capitalism. For all of its hundred-plus years, it has drawn on the energies of more dynamic but marginal and ephemeral social movements to renew itself and in particular to get its professional cadres re-elected to parliament. That is the real, thoroughly dispiriting, historical outcome of ‘Labour’s capacity … to draw from the popular energies of very different movements outside the party’.

The Labour Party was founded on the back of the great upsurge in mass, ‘national-popular’, democratic activism in late-Victorian, still overwhelmingly industrial Britain. Even then, it managed to combine all sorts of other ideological components from what was at that time an extraordinarily rich ‘civil society’, such as radical Liberalism and Marxism, Methodism and pacifism, feminism and male chauvinism, imperialism and internationalism, voluntarism and statism, municipalism and parliamentarism — all these and more, in often dynamic contradiction. This was the celebrated (and much admired elsewhere) ‘broad church’ approach to working class politics, with deep roots in daily life and about as close as Labour ever came to a genuinely ‘hegemonic’ strategy for taking and exercising power. Then came Ramsay MacDonald, the first in an almost pathological pattern of ‘betrayal’ and dashed expectations, which forms the sorry emotional leitmotif of Labour history.

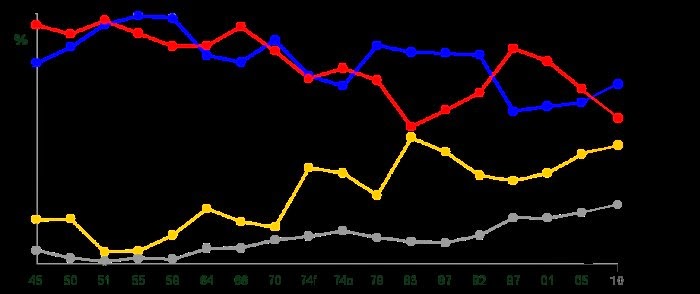

The travails of the 1920s and ’30s at least helped to focus and popularise the party, to lay the basis for the post-war heyday of Labourism. This culminated in the highest ever popular Labour vote in 1951. Even then, there were ‘betrayals’ and disappointments along the way (Oswald Mosley and his ‘New Party’, Stafford ‘austerity’ Cripps and eventually the labourist patron saint Nye Bevan himself). Labour’s failures were barely offset by the great (similarly mythologically resonant and seriously flawed) labourist achievements of the NHS and the welfare state. And of course, though Labour got its highest ever vote in 1951, it lost the general election to the new ‘one nation’ Conservatives. Labour’s most ambitious attempt at ‘technocratic managerialism’ by Harold Wilson, underpinned and propelled by Crosland’s social-democratic ‘revisionism’ and the corporatism represented by ‘beer and sandwiches at number 10’ for trade union barons, foundered on its own internal contradictions amid the capitalist crises of the 1960s and 70s.

Along the way, there were repeated attempts by Labour to tap into new popular energies, such as the war-time ‘Dunkirk spirit’ of national togetherness; or the ‘scholarship generation’ of 1950s working class intellectuals borne along on their parents’ hard-won affluence and aspirations; or their younger brothers and sisters ebulliently engaged in the evenements of 1968 and after. I have a particular interest in the latter, as the final example of the ‘broad’ left attempting a truly hegemonic take on British political economy, via the social contract and the alternative economic strategy in its first, pre-Bennite form. It swiftly retreated from mass politics into the far more comfortable settings of trade union office, seminar room and ‘left-leaning’ newspaper columns.

In the 1980s, Labourism tried several different takes on the ‘new social forces’ derived from ‘the politics of identity’ which Stuart Hall and others were helping to articulate. Bennism had a go first, with an opening to the non-Labour left of feminists, black and gay activists. This generally ended in tears when they rubbed other, more straight-laced members of ‘the broad church’ up the wrong way, so to speak. As Thatcher embarked on her full-frontal mid-80s assault on ‘loony leftism’, we embarked on yet another round of recrimination and disillusionment. The ‘soft left’ was in part an honest attempt to salvage something from the wreckage. Egged on by Kinnock’s ‘favourite Marxist’ Eric Hobsbawm, and by the Euro-communists’ favourite Labourist Bryan Gould, it came perilously close to a thoughtfully reformist, outward looking and alliance building politics, but at its big soppy heart Labour remained a party of tribalists. All talk of pacts and alliances fell away when they sensed that with professional advertising and media management to gloss up the product, Labour could go it alone just like in 1945. Finally, as we’ve seen, New Labour took off on its own messianic journey into ‘New Times’.

My analysis is open to challenge on a number of counts. Labour has in its hundred-plus years achieved some genuine amelioration in the living conditions of the industrial working class. Imagine what the last century would have been like if capitalism had been able to exercise the free hand it has now. Unemployment and related benefits, state pensions, some measure of protection against injury and discrimination at work, comprehensive education (even post-war access to grammar schools for bright poor kids like me) and social housing are all real consolations for the miseries inflicted by the ‘free market’.

New Labour continues to devise and to offer its own consolations. Just recently I heard one of its advocates argue that the slush-funds of ‘local regeneration’ and ‘social inclusion’ represented a further, proud example of Labour providing compensatory ‘access to the state’ in addressing ‘market failure’. Throw money at anything, I would respond, and it will undoubtedly feel better for a while. Ask any lottery winner. But, as is all too obvious now, these schemes and fixes are easily undermined or even swept away when they are judged ‘unaffordable’. All the ‘new deals’ and ‘sure starts’ will not survive the next serious recession and round of public spending cuts, let alone a New Tory sweep-out. Besides, they have never provided any basis for a real challenge for power, or rather in Gramsci’s much more resonant term ‘hegemony’.

Then there’s the historical absence of much else of value in British working class politics. Even Labour’s staunchest critics have felt forced to accept that it has historically been ‘the mass party of the British working class’. They have usually campaigned for some wider social ferment, which would force the party to adopt ‘more progressive policies’. For much of its history, Labour’s only semi-serious political rival, the Communist Party of Great Britain, worked to a strategy of ‘militant labourism’. This would (in ways never entirely spelt out) bring along ‘a Labour government of a new type’. Even Hall’s (and especially his Marxism Today stable-mate Hobsbawm’s) 1980s critiques were aimed (however tetchily) at eventually restoring Labour’s political vigour. What is most striking now about the history of the CPGB is just how deferential it was towards Labour, in all its phases and across all its factions, rather than seeking seriously and strategically (like other more effective European communist parties) to displace their labourist rivals or at least force them to develop a coherent social democracy.

There have been, as I’ve already noted, some genuinely interesting and creative attempts to connect the Labour Party with wider movements and trends in British society, even if they remained isolated and tentative and have almost always resulted in bad feeling all round. And there was always the powerful argument that any political initiative outside of the Labour Party would inevitably end in narrow, shrinking sectarianism and ‘being confined to the political wilderness’. There are plenty of generally very depressing examples of this too, including the CPGB, and thus a serious pro-Labour case to answer. Apart from anything else, there are plenty of ‘good people’ still in and around the Labour Party (many of them clustered around Compass) who would place themselves within our self-styled ‘democratic left’ but still need persuading that Labour is really and truly dying.

I would argue now that, for a whole range of reasons, Labour is no longer the mass party of the British working class, not least because its leadership has decided (understandably) that it doesn’t want it to be. This sounds obvious but it needs spelling out, and in historical terms is the primary explanation for Labourism’s long decline. The long-term retreat and fragmentation of the working class and the breakdown of its tribal habits and loyalties was one of the primary reasons for the New Labour manoeuvre. Voting and (especially) membership figures attest to the party’s decline as an active political (or even social and cultural) presence in the real, everyday world. Hence the reliance by New Labour on ‘spin’, through a generally compliant or appeased media, as the only remaining means of reaching its ‘public’. In a very practical sense the Labour Party barely any longer exists ‘on the ground’ where most of us spend our daily, increasingly de-politicised, lives.

This surely is the real but barely commented-upon reason for Labour’s fawning reliance on rich businessmen’s money, donated or loaned. Labour is simply not receiving enough in membership fees to pay for the operation of a modern, media-dependent political party, let alone making up for dwindling and politically uncomfortable trade union support. The Jowell/Mills and ‘loans for peerages’ affairs attest to the real sorry organisational state of the party, but also to the residual ethical framework of labourism — a large part of the public revulsion with Labour is made up of scorn for the bosses’ ill-gotten gains. How can ‘our people’ be so cosy with ‘them’? That’s why nobody’s much bothered about the Tories’ much greater reliance on handouts from the plutocrats of bandit capitalism, because it’s what we expect. New Labour’s ultimate failure lies in being unable to shake off the ethical straitjacket of labourism, while the real political agency of the party continues to shrivel.

So what do we do now? We could usefully revisit one of the central arguments of the first, late-1950s New Left — that Labourism is an obstacle to the wider social ferment we need in order to bring about progressive change in Britain. The modern democratic impulses at work in Britain, beyond the sterile pantomime of parliament and its regional and local clones, are going on despite not because of Labour. Tribally, instinctively, mythologically, it remains deeply suspicious of Hall’s ‘movements outside the party which it did not — could not — set in play, and which it cannot therefore administer’. It pains me to say it, but the examples of genuinely democratic developments I am most professionally familiar with from the last 20 years (health and social care for people with HIV/AIDS, for instance, or tenant participation in housing) received far more government support, financial and moral, under the Tories than Labour.

Thatcherism was (and remains, in its ‘transformist’ adaptations) a many-faceted beast . In its urge to ‘roll back the frontiers of the state’, it left quite a lot of space for new ways of providing and receiving services, not just in the deregulated private market but also in the remaining, generally battered public sector. It was possible to deploy Thatcherism’s anti-statist thrust in some surprisingly creative, invigorating and genuinely innovative ways. We felt ‘freer’, even if only to harm ourselves and those around us. We could be ‘who we really are’, even if that ultimately meant being confined to particular, comfortable, sealed boxes of sexual, gender, ‘cultural’ or ethnic identity, locked in an uneasy stand-off in our supposedly diversifying society. We could choose our lifestyles and circumstances, even if the very exercise of choice consigned others to deeper subordination. We could take pretty much exclusive responsibility for the upbringing of our children, even if it took extraordinary dedication and sacrifice to do it half-well, and the class-status and confidence to avoid the ‘protective’ scrutiny of the moral agents of the soft state. We could purchase anything — any kind of pleasure, our own homes and cars, shares in privatised utilities, high quality education and health care, ‘fancy foreign holidays’, above all our own social identities, that is, who those around us thought we were.

New Labour of course accepts all this, but in an oddly joyless, fastidious and ultimately begrudging spirit. The ‘celebration’ of Thatcherism is the aspect of the ‘New Times’ legacy they bridle most at. New Labour accepted the invitation to the party, but they’re still standing in the corner with their ties and belts done up tight, watching everyone else enjoy themselves. Really and truly, New Labour disapproves of Thatcherism’s freedoms, what Stuart Hall has called its license to ‘hustle’. It has, by contrast, rushed to accommodate and deepen all the ‘regressive’ elements of Thatcherite ‘modernisation’ — globalisation above all, but also its closely related project of ‘authoritarian populism’. In its drive to get us all ‘ready for market’, it shows growing disregard not just for the traditional niceties of the liberal state but for any kind of difference or dissent beyond those officially sanctioned within its own ‘respect agenda’ . It is even more inclined than in 1987, when Stuart Hall wrote these words, to regard as ‘subversive’ anything which ‘doesn’t proceed out of the mouths of the Labour leadership.’ And again, why should we be surprised? Personal liberty, in its deeply English (and highly, even globally, attractive) form of comic irreverence and wilful individualism, has always been inimical to the Labourist tradition of dour conformity.

The problem for the democratic left is that the actual, final death of the Labour Party, as an organisation of people with deep vested interests in its survival, doesn’t look like happening any time soon. Labourism as an ideological strand is clearly exhausted but the Labour Party itself has powerful organisational life-support systems, not least the networks of local and national state patronage it still controls. The Labour Party simply is, even if it has lost any sense of where it might be going and any historic mission beyond the vacuities of the Third Way. The real question for us then is — what can we do to help kill it off?

There are epochal processes at work within British politics, which seriously threaten the Labour Party’s survival. The decline of popular faith and involvement in electoral politics is eroding its own popular base. Very few local Labour Parties nowadays are capable of a ‘total canvass’ of their wards, which was always the pre-requisite for the regular, well-oiled Labour ritual of ‘getting out the vote’. The party has officially lost more than half its membership since 1997, over and above all those members (like my wife) who stopped paying dues years ago but still receive members’ mailings and are presumably still counted as members because they never got round to actively resigning. As it loses local council seats, not to mention local ‘activists’, there are fewer local councillors to do the actual donkey work. The policy/lobby group Compass shows signs of intelligent life, but they are about the only ones around the Labour Party. It remains to be seen how much long-term impact or influence they have.

The decline of interest in electoral and party politics among younger people has been well documented. They are simply not acquiring the habits of ‘civic duty’ of previous generations. However, that’s not to say they are politically uninterested. In my experience of parenting and teaching some of them, I find a hunger for insight and explanation to help make sense of the bewildering world around us. They very often end up looking in the wrong places, embarking on forms of ‘political tourism’ and returning from their global gap years with the simplistic, unsustainable pieties of ‘anti-capitalism’. But they are not in any numbers going anywhere near the Labour Party or anything else which might engage them in the hum-drum but utterly crucial routines of national-popular politics.

We may just at the next election, by a fortuitous combination of luck and tactical design, arrive at a hung Parliament. That’s assuming that the imminent deterioration in economic and political circumstances, which have so far spared New Labour any serious test, doesn’t deliver something nastier. Then, if the notoriously slippery Lib Dems can hold their nerve and insist on Proportional Representation, we might just see the beginnings of a properly democratic, modern political system, which genuinely reflects the real currents of popular feeling. That would include all those of us on the democratic left who finally, historically, have had enough of Labourism, the Labour Party and all its ways and works.

That’s a relatively optimistic short-term view. I don’t share it — far more likely is a New Tory Cameron government, sooner or later displaced by some form of neo-Thatcherism, which remains the strongest ideological impulse in Britain. But all of that should be of secondary concern to anyone who wants to see real, deep, meaningfully left wing transformation of British society in all its cultural, social, political and economic aspects. We need a new political formation, which will survive the demise of the Labour Party, and hopefully play an active, purposeful part in the long overdue historical ‘project’ of killing it off.