Some years ago in a time BTC (Before The Crash), a group of

us wrote a booklet entitled Feelbad

Britain. (Available at http://www.hegemonics.co.uk/docs/feelbad-britain.pdf).

It received mild interest and then passed into the oblivion reserved for small

political tracts. One sentence from its first paragraph sums up its content: Twenty-first century Britain, our country,

is afflicted with a deep-seated and widespread social malaise. Since that

distant past, this malaise has deepened. One obvious factor is the revelation

that our high-street banks, once pillars of respectability, are nests of crooks

who have managed to steal billions of pounds without any retribution. Another

is the ongoing disclosing of just how deep rooted has been a culture of sexual

depravity and paedophilia amongst once-revered entertainers and politicians.

Perhaps the defining revelation is that an allegedly demented paedophile was

able a few weeks ago to sign his name to a letter requesting leave-of-absence

from the institution of which he remains a member: the House of Lords.

Presumably his advisors thought it might be embarrassing for him to continue to

sign to collect his £300/day ‘expenses’. Truly, England has become a sad and

dispiriting country.

Meanwhile, amidst this malaise, a suitably sad and

dispirited election campaign is underway. On the Conservative side, this lack

of any spirit is understandable. If one accepts that there are only two kinds

of election campaign: steady as she goes and throw the rascals out then clearly

they have to be bound by the former and unexciting slogan. Steady as she goes,

chaps, careful not rock the boat, we’ve got the wind in our sails, easy does

it… (I think that’s enough nautical stuff). Even so, Cameron has seemed so

lack-lustre as to require a special boost of amphetamines to inject just a bit

of dash into his manner.

The issue really is just why the ‘throw the rascals out’

Labour campaign has been so pitiful. Just why these devotees of the West Wing with their expensive American

advisers and their months of preparation have managed not just to be totally

devoid of any spirit but also to be so inept. These, after all, are the chumps

who lost Scotland, the heartland of the labour movement, Red Clyde and all

that. Say it very loud: these are the chumps who LOST SCOTLAND.

It is not as though there were not plenty of warning signs. The

electoral system for the Scottish Parliament could have been designed expressly

to stop any one party dominating but in 2011, the SNP did win an overall

majority. Then they came within touching distance of succeeding in the

referendum. Then, instead of realising that by siding so openly with the Tories

as pro-Union they had poisoned their reputation, that when, last year, the

leader of the Scottish Labour Party, Johann Lamont, resigned saying that

Scottish Labour was treated “like a branch office

of London”, she was replaced not by an MSP but a political bruiser from

Westminster. At the time, Henry McLeish, another former Labour first minister, said

that Scottish Labour supporters no longer know “what the party stands for” and that it had given “enormous ground to the SNP unnecessarily”.

But still the chumps carried on oblivious.

It could still all be a dream and we could wake up on 8 May

and find that it was the same-old two-party system. But the Scottish polls all

suggest otherwise. The result of the inevitable bargaining over a minority

government will clearly fill the columns. But another, underlying issue will

also arise; can the Labour Party survive the debacle of losing Scotland. In

terms of simple arithmetic, the answer is yes, it can survive without Scotland.

In 1997, it won with a UK majority of 179 so even losing 41 seats in Scotland

would have left it with a massive majority. It would even have won in 2005

though with a majority of barely 20. In a sense, the arithmetic is even better

if one takes into account the fact that Scotland is over-represented with

several small seats. It could even, looking to the future, survive the loss of

Wales if one follows the idea that if Scotland goes then perhaps Wales will

also see the advantage of having a progressive regional party look after its

interests. In 2010, Labour won 29 of 40 Parliamentary seats there though with a

historically low share of the vote, 36.3%. In principle, taking 1997 as a

marker, it could still gain a majority of close to 100 even if it were to be

wiped out in both Scotland and Wales. Even the result in 2005, a Labour

majority of 66 would be almost a dead-heat without Celtic votes.

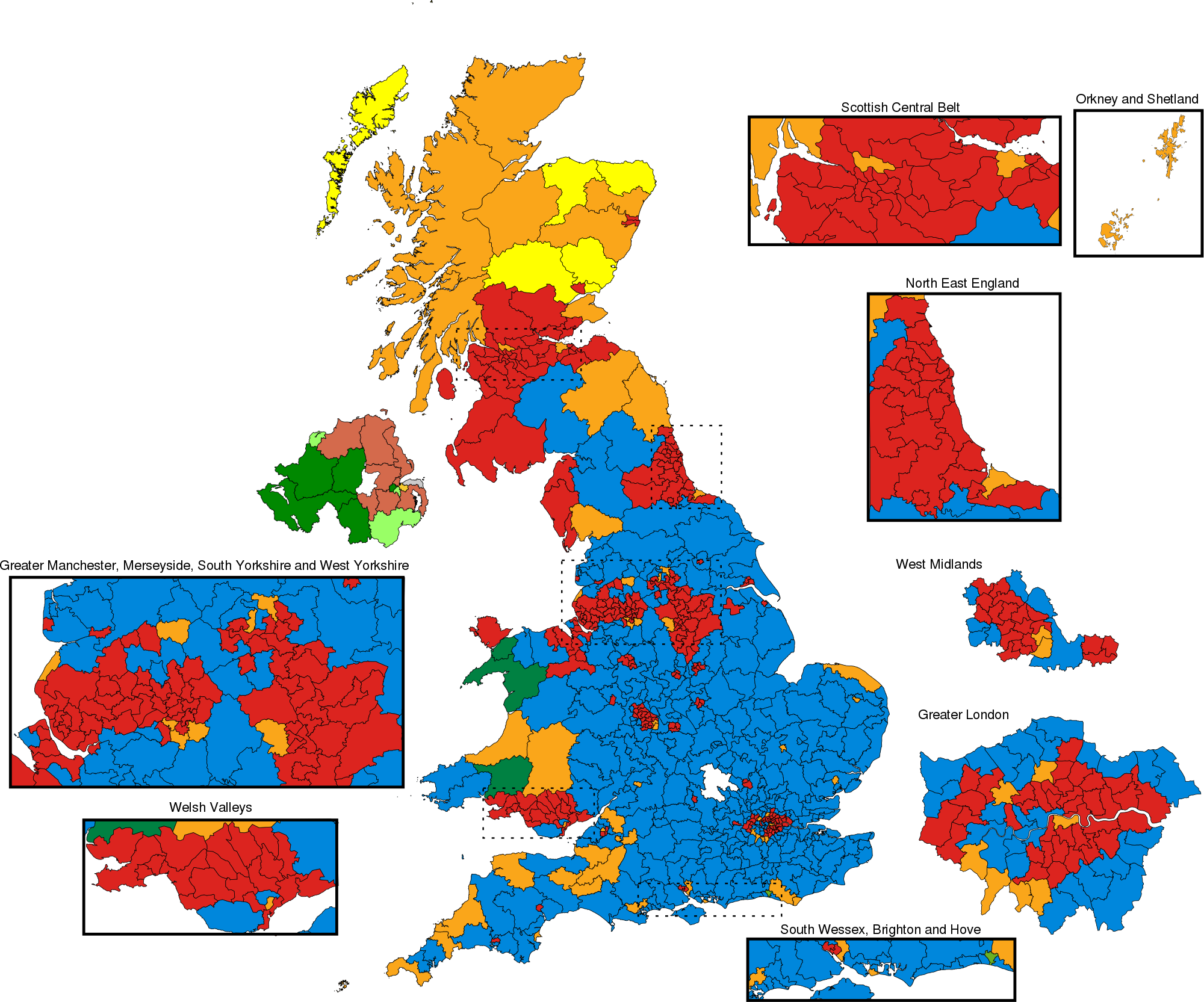

To appreciate what this would mean requires some graphics.

Electoral Map, 1997

This is the best that Labour has received in modern times.

And here is the map from the other famous victory in 1945 when Labour had a

majority of 150.

UK in 1945

general election

Finally, let’s look at the 2010 result.

UK in 2010

election

These three show how dramatically concentrated Labour has

become regionally within England even in the miraculous victory of 1997

compared with 1945 when it actually won fewer seats. Since 1945, entire regions, notably East

Anglia and the east Midlands drifting down to London have become effective

no-go areas for Labour. In 2005, there was almost dead-heat in England as shown

below, achieved by Labour holding on to seats in the west Midlands and this

could be repeated in a future election. It is almost certainly the best it can

hope for from this election.

In other words, Labour can survive and even win a

Parliamentary majority without the Celtic votes. However, it would become

essentially a regional party ruling over the entire U.K. as well as Northern

Ireland from a swathe of northern England and central London. This would be more difficult once the

slow-motion Electoral Commission had regularised seats boundaries but still not

impossible. The question is, even if this electoral manoeuvre could be

successfully carried through, is such a regional domination politically, let

alone democratically, possible. The problem is exacerbated by the likely issue

that Labour would win a majority of the seats but not of the total vote.

England is not a country prone to civil war but a scenario of Labour ruling

from such a confined English base would seem to set a possible scenario for

another one.

Electoral Map

of England in 2005 general election

Unless there is a sea-change in the next five days, the

result of this election seems likely to raise a whole raft of questions, essentially

concerning legitimacy. These could arise almost immediately if, as present

rhetoric suggests, Labour would try to govern without making any kind of

agreement with the regional party which has just wiped it out in one part of

the U.K. The same issue, though as a kind of mirror-image, will come about if

the Conservatives push ahead with their commitment to limit parliamentary votes

on issues on which Scotland has devolved powers to English M.P.s Although

Labour has largely tried to avoid the issue, it was in fact first voiced by a

Labour M.P., Tam Dalyell, back in 1977 and became known thereafter as The West

Lothian Question after Dalyell’s Scottish constituency.

This problem has been avoided by the three main parties

largely because they pretend that they are genuinely national bodies choosing

to follow U.K. national sentiment in the belief that Northern Ireland is a kind

of foreign country with its own mysterious and potentially frightening

political governance. The Tories have moved closest to accepting that they are

basically an English party having been wiped out themselves in Scotland in 1997.

It is hard to remember that up to 1987, the Tories had 21 seats in Scotland and

were only overtaken by Labour there in 1955 when it still operated as the

Unionist Party before merging with the Conservative Party of England and Wales.

The Liberal Democrats have an odd, historically based

regional pattern with a geographical base in the South West followed by patches

in the North West, Scotland and Wales which essentially follow the bases of the

old Liberal Party. Given that most these last are likely to go in this election,

their regional base will become quite clear.

The regional basis of Labour once it has lost Scotland and,

potentially Wales, and having no real links with any Northern Ireland party will

pose it with a huge problem given that it has become a party essentially run from

a London-based machine. Only Manchester outside of London still possesses

anything like a regional power-base. One of the most difficult issues for

Labour, if it does form a minority government, is what to do about DevoManc

given that it was negotiated directly by local Labour bosses without,

apparently, any involvement of the London leadership. If similar powers to that

accorded to Greater Manchester are passed to other cities, mostly northern,

then it will be seen throughout the rest of England as a way of privileging

Labour’s northern base. If it lets Manchester proceed on its own then it will

enrage leaders in cities such as Leeds, Newcastle and Liverpool.

The fact is that Labour has become a regional party but

without the local, regional dynamism which propels other regional-based

grouping in countries such as Spain and Italy. And, of course, its ‘region’ has

no name or political identity other than ‘up there’ or the ‘grim north’. Older

Labour members sometimes nostalgically recall the days, usually the 70s and

early 80s, when local northern Labour constituencies had some real life and

sense of social purpose. Now they are just efficiently organised electoral machines

with no role for members other than a little electoral activity.

Must Labour die? Well, in its current form, probably unless

the chumps who lost Scotland manage some exceptionally clever reorganising.

There will undoubtedly by some vicious infighting inside the leadership

especially as beasts such as Douglas Alexander and Jim Murphy will be wandering

about wondering how to get back on to the gravy-train which has given life for

so long. The chances of a new and brighter party leadership emerging from the

wreck are small particularly if, because of the vagaries of the British electoral

system, they have the chance of forming a minority government provided, of course,

they manage to eat humble pie and deal with the SNP. Good luck on that one.

One final thought. The Green Party has always had a separate

organisation in Scotland. In England and Wales, they could emerge being able to

claim that they are the only genuinely national party not rooted in one region,

north, south, east or west. Not quite sure how that one will pan out either.