Early in 2014 in a South African journal,The Thinker (Q1, 2014),

Thabo Mbeki laid out his vision for the future of the progressive movement in

Africa. The core of this agenda, was “establishing

genuinely democratic systems of government, including accountable State systems”.

He is harsh about the reality of democracy in many African countries in which “State systems have been reduced to a

patrimony of a predatory elite, controlled by its self-serving ‘professional

political class’” “Thus”, he

continues, “does the putative democratic

state become a social institution which serves the interests of a

‘rent-seeking’ elite whose goals amount to no more than preserving its

political power and using this power to extract the ‘rent’ which ensures its

enrichment”

Harsh words indeed, though ones which have

become almost a cliché with respect to the governance of many African states.

Yet, by an odd coincidence, at around same time, The Economist, august journal of the western business elite, had a

front-page splash “What’s gone wrong with

democracy?”,[i]

the title of a long essay inside which opened by suggesting “that democracy is going through a difficult

time. Where autocrats have been driven from office, their opponents have mostly

failed to create viable democratic regimes. Even in established democracies,

flaws in the system have become worryingly visible and disillusion with

politics is rife. Yet a few years ago democracy looked as though it would

dominate the world.” The piece ends with the quotation from a past US President

often found in The Economist that “democracy never lasts long. It wastes,

exhausts and murders itself. There was never a democracy yet that did not

commit suicide” John Adams wrote this in 1814 and it is unclear as to

precisely what he was referring. There had been a brief flourishing of

democratic intent in France a few years before, quickly snuffed out, and there

had been the original ‘democracy’ in Athens copied by a few other Greek

city-states around the fourth century BC in which, it is believed, around 15% of

the population took part. There was, of course, the Roman Republic which we

know ended badly on the Ides of March and also the Republic of Geneva about

which the less said the better. Adams in fact had precious little evidence on

which to base his assertion and, of course, it would not have occurred to him

that a country whose franchise excluded all women and those males held in

servitude could not be seen as a democracy. Even so, recent history suggests

that he had a point given that in 2014 alone, three elected governments were

overthrown and replaced by self-appointed cliques.

Doubts about the state of democracy are not

confined to right-wing journals. The eminent left historian, Perry Anderson,

recently published a coruscating essay mainly about the corruption of Italian

democracy but which opened with a lament for European democracy in general.[ii]

Europe is ill. How seriously, and why,

are matters not always easy to judge. But among the symptoms three are

conspicuous and inter-related. The first, and most familiar, is the

degenerative drift of democracy across the continent, ... Referendums are

regularly overturned, if they cross the will of the rulers. Voters whose views

are scorned by elites shun the assembly that nominally represents them, turnout

falling with each successive election... executives domesticate or manipulate

legislatures with greater ease; parties lose members; voters lose belief that

they count, as political choices narrow and promises of difference on the

hustings dwindle or vanish in office.

He

continues with a roll-call of distinguished European politicians who have been

implicated in various ways in huge corruption scandals amongst them Helmut

Kohl, Jacques Chirac, Gerhard Schröder, Horst Köhler (former head of the IMF), Christine

Lagarde (current head of the IMF), Bertie Ahern, (past Irish prime-minister),

Mariano Rajoy (current Spanish prime-minister) and on through Greece, Turkey

and the U.K. The sums involved are not small: Helmut Kohl was found to have

amassed some two million Deutschmarks from donors whose names he refused to

reveal. Not one of this illustrious roll-call has so far been called to account

though Lagarde is currently under criminal investigation, something which seems

not to impede her job ruling the global financial system.

Nor

is the problem of dynastic political elites any preserve of Africa. Arguably

the most important democracy in the world, certainly the largest, is India in

which 814 million people went to the polls in May, 2014. These elections were

widely publicised as resulting in the overthrow of the Gandhi family which had

ruled India for four generations and bringing the Bharatiya Janata Party to

power led by a man of humble origins with no family connections to assist him.

However, as Patrick French has shown in a recent book,

India: a Portrait,

[iii]

nearly 30% of members of the Indian parliament, the Lok Sabha, were connected

directly by family to their political posts whilst, startlingly, all members

under 30 were the children of former politicians. There is little sign of voter

disillusion with electoral democracy in India with the 2014 election showing

the highest ever turnout at 66.4%, a respectably high figure for a country with

such a huge, poor rural sector. However, the importance of dynastic connections

suggests that even in this vibrant democracy there are some problems.

In

the USA, the democratic problem is, as always, money and its connections with

power. Efforts to limit the amount of money which individuals or corporations

could spend supporting political candidates have been regularly ruled as

unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. According to the respected journalist,

Gary Younge:

In a system

where money is considered speech, and corporations are people, this trend is

inevitable. Elections become not a system of participatory engagement

determining how the country is run, but the best democratic charade that money

can buy. People get a vote; but only once money has decided whom they can

vote for and what the agenda should be. The result is a plutocracy that

operates according to the golden rule: that those who have the gold make the

rules.[iv]

Once,

powerful unions were able provide some counterbalancing finance to that of

corporate interests. However, the decline of unions and the almost exponential

growth in the scale of expenditure on elections have greatly reduced this

influence. Even so, American democracy has always been a bit rough-and-ready

and tinged with corruption, though the scale of this may be increasing, whilst

the very decentralised nature of US politics does provide scope for some

genuine democratic initiative. The real

centre of the democratic ‘crisis’ lies in Europe.

It

is sometimes forgotten just how recent democracy is in much of Europe and how

fractured has been its history. Only Sweden and the UK can really claim to have

enjoyed unbroken democratic governance since the late nineteenth century with

the gradual extension of the franchise to include women as well as the working

class less than a hundred years ago. Even so, the disappearance of fascism from

southern Europe in the 1970s followed by the emergence of parliamentary

democracy in the Communist countries of Eastern Europe in the 1990s seemed to

suggest that this form of governance was inevitable and immutable, so much so

that in 1992, Francis Fukuyama was able to pronounce that:

What we may be witnessing is

not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war

history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's

ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.[v]

Fukuyama

has in recent years rather backtracked from this position but only at the

margins despite the conspicuous failure of the efforts of the USA to impose

liberal democracy on Iraq and Afghanistan. Why then the sense of a democratic

crisis particularly in Europe? In a number of ways it is the culmination of two

trends which have been developing for years, indeed decades.

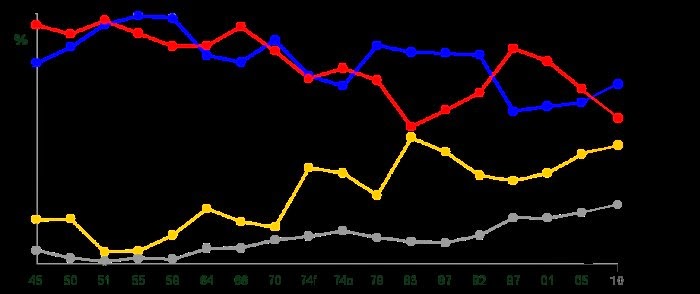

The

first is the gradual decline of public involvement and interest in the

processes of electoral democracy. The most obvious of these is participation in

elections, something which appeared to have stabilised in Europe in a period

from the 1950s through to the 1980s at around 80-85%.

After this decade there was a slow but

steady decline throughout Europe, something which seems to have accelerated

into this century. In 2001, the UK had the lowest turnout since the advent of

mass democracy whilst France fell to a record low of 60.4% in 2007. A raft of

other countries, including Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Spain and Finland, have

also recorded record lows. A second indicator of decline in involvement is increasing

voting volatility, which is the number of voters who shift their party preferences

around from election to election. This lack of stability in voting preference

suggests disillusion with the democratic process. A third and in some ways the

most significant, has been a major decline in the membership of political

parties. The U.K. is the most extreme example with an aggregate loss in party

membership over 1.1 million between 1980 and 2009, a drop of 68% but most other

European countries have seen falls of 30-50%. There does not seem to be any

left/right bias in this fall; just a uniform decline in participation.

This

fall in membership has been accompanied and may be partly caused by the gradual

hollowing out of the meaning of ‘membership’ which has occurred in most

European parties. Outside of small-town direct democracy, political parties are

the key agency of modern participatory democracy, acting as they do to

formulate policies and to promote leaders. They provide the collective

participation necessary to provide elected governments with some kind of

bedrock in the popular will.

Essentially,

this hollowing-out process involves a transformation of ‘members’ into ‘active

supporters’, that is people who are willing to assist with campaigning at

elections by delivering leaflets and so on but who have little or no influence

in the formation of party policy or the development of its leadership. This

loss is mirrored by exactly the same phenomenon which was noted by Mbeki, the

growth of a self-serving

‘professional political class’ composed of people who have made politics

their career from an early age and have been promoted up the party ladder,

often by becoming advisers to established politicians or, initially, by using

family contacts. This ‘political class’ has become enmeshed with business

interests, particularly in the financial sector, and with state agencies to

form a circulating but sealed elite group who have largely gone to the same

schools and universities. So for many voters all main parties ‘are the same’

thus making a mockery of multi-party democracy.

The

other side of the collapse of the membership-based party has been the growth of

‘wild’ parties, that is parties with no historical base but which suddenly

achieve electoral success based on popular discontent with the established

parties. Syriza in Greece which polled only 4%

of the national vote in 2009, became the main opposition only in 2012, received

27% of the vote in the European elections and has now won a stunning electoral victory in national elections with the rightwing governing party

down to 23%, is the prime example of this phenomenon

together with the U.K. Independence Party which topped the vote in the European

elections also with 27%.

In Italy, the Five Star Party founded by the comedian,

Beppo Grillo, astonished the establishment by obtaining over 25% of the popular

vote in 2013 national elections and over 21% in the 2014 European elections even

though the party has been racked by rows over the alleged autocratic control of

its founder. Both Syriza and the Five Star Party can be seen as left-radical

but the more dominant trend in the growth of ‘wild’ parties has been that of

the far-right anti-immigration groups such as UKIP. In the 2014 European

election, far-right parties topped the poll in Denmark (the People’s Party with

26.6%) and France (National Front, 25.0%) whilst for the first time,

more or less

openly neo-Nazi parties – the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) and

the Greek Golden Dawn (XA) – for the first time entered the European

Parliament. This movement to the right is far from uniform over Europe though

as a perceptive analysis is the Washington Post noted, “the abysmal performance of radical right

parties in Eastern Europe is that mainstream right-wing parties in the region

leave little space for the far right, given their authoritarian, nativist and

populist discourse.”[vii]

The common feature of all the right-wing parties is their vituperative hatred

of immigrants, the most disturbing of all the political portents in Europe.

The

second trend which mirrors the first has been the growth in importance of

supranational bodies, notably the European Commission but including such as the

IMF, which have little or no democratic basis but which exert power within

countries comparable to or exceeding national government. Added to these are

the other array of supranational bodies, the international corporations in

particular financial ones which answer to no democratic authority at all. A

prime example of the combination of these two power-bases is the pending

Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, an exceedingly complex treaty

to be struck between the EU and the US government which amongst other things

will enable transnational corporations to sue national governments inside the

EU for any unilateral regulatory process which damages the interests of the

corporation. National legislatures will have no say in agreeing in this package

and although the European Parliament will vote on the whole deal, it will have

no power to amend it.

A

consequence of this bipartite congruence is that increasingly, national

governments are seen as lacking many elements of real power. The failure to

control the international financial markets even though their collapse in 2008

required bailouts by nation states is a prime example of this. The result is a

further decline in interest in electing these supine governments.

The

‘democratic deficit’ of the EU has long been a topic of continual if

ineffective debate. Essentially, the problem has always been that closer

national ties have always had a political objectives but ones disguised as

economic matters. Initially these could be seen as the benign hope that closer

trade links would extinguish any possibility of the wars between European

states which had effectively blighted the first half of the twentieth century.

However, the changes in the name of this economic system, the Coal and Steel

Community (1950), the European Economic Community (1957), the European

Community (1993), and, finally, the European Union (2007) precisely mapped the

gradual, if still largely implicit, shift towards political unity as well as

the enlargement of the community which now includes 27 countries, quadrupling

its original size, all without much in the way of democratic agreement by the

electorate of the member countries.

The

gradual evolution of the EU into a blatantly political body made a step jump in

1993 with the Maastricht Treaty which set up the euro as a common currency and

established the so-called ‘three pillars of economics, foreign and military

cooperation and home and judicial affairs, all largely undefined in the usual way

of using generalised phrases which could later be turned into specific policy

actions without any democratic basis. Maastricht was remodelled and refined by

a series of further treaties (Amsterdam, 1997, Nice 2001, Lisbon 2007), all

complex and all pushed through with almost no popular democratic approval.

Nearly all attempts to put these treaties to popular vote have resulted in

debacle. In 1992, the Danes rejected Maastricht and the French very nearly did

so. In 2007, the only country to risk a referendum on the Lisbon Treaty,

Ireland, had it rejected and was forced

to run another vote in which every screw was put on the electorate to vote Yes

or, allegedly, risk oblivion. In fact real oblivion came in 2008 when the

financial crisis resulted in the European Commission, backed by the European

Central Bank and the IMF, stepping in to dictate economic policy in Greece,

Ireland and most of southern Europe, insisting that elected governments be

replaced by appointed technocratic leaders if they failed in their duty apply

the financial austerity necessary to save the European banking system,

something which actually happened in Greece and Italy.

It

is a an odd irony that the problem of the democratic legitimacy of the EU is

widely recognised even within the autocratic corridors of the European

Commission just as they are being filled with the appointed new Commissioners

who epitomise the problem. Even more ironic is that any move to alter the

current position would almost certainly require a treaty change, something

which is very unlikely to get past popular opinion in several EU members whose

populations are itching to slap down Brussels if not to actually leave. It

seems likely that the U.K., always the most eurosceptic member, will have some

form of referendum on membership in the next three years which could easily

result in the U.K.’s departure and precipitate further disorder. Meanwhile, the

imposed austerity programmes in southern Europe which have led to economic

stagnation continue to fester.

The

root causes of the decline in democratic participation throughout Europe are

hard to uncover. However it is striking that the moment in which decline really

begins is also that in which neoliberal individualism bit back against the

collectivism which had characterised Europe throughout the last century up the

1980s. As a recent book by Peter Weir puts it puts it when discussing the decline of the mass party:

A

tendency to dissipation and fragmentation also marks the

broader organisational environment within which the classic mass parties used

to nest. As workers’ parties, or as religious parties, the mass organisations

in Europe rarely stood on their own but constituted just the core element

within a wider and more complex organizational network of trade unions,

churches and so on. Beyond the socialist and religious parties, additional

networks ... combined with political organisations to create a generalized

pattern of social and political segmentation that helped root the parties in

the society and to stabilize and distinguish their electorates. Over the past

thirty years, however, these broader networks have been breaking up ... With

the increasing individualization of society, traditional collective identities

and organizational affiliations count for less, including those that once

formed part of party-centred networks.[viii]

It

is a depressing but undeniably plausible conjecture to link decline in the most

fundamental aspect of progressive advance in the twentieth century, mass

electoral democracy, with the resurgence of the most regressive, neo-liberal

markets. It does suggest that reversing the decline in electoral democracy will

need more than some simple turnaround in party policy. Speculation as to just

where this dual crisis of democratic legitimacy is going would double the size

of this essay and lead precisely no-where.

There are some dark forces gathering and it is almost inevitable that

several countries are going to face serious political challenges from

anti-immigration groups. There are some vibrant progressive forces which

emerged, notably Syriza in Greece, but they are internationally isolated and

have so-far failed to find a coherent strategic policy.

In

the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, there is currently a temporary

exhibition celebrating the shared cultural history of Greece and Italy. One

exhibit is a small relief of a “Mourning Athena”. The accompanying description

of this concludes by suggesting that “the contemplative expression of Athena

reflects the sceptical way in which we should view the current political

situation in Europe” When doubts about Europe’s political future appear

inscribed in archaeological analysis we

know that we are in trouble.

(First published in The Thinker, December, 2014)

[i] The Economist, 1 March 2014

[ii] London Review of Books, 22 May 2014, London

[iii] Patrick French,

India: a Portrait, Penguin, 2012, ISBN

0141041579

[vi] Most of the

quantitative measures in this section have been taken without further

attribution from Peter Weir,

Ruling the

Void, Verso, London, 2013 ISBN

1844673243